How Canada’s indigenous people stood up to the fishing industry – and brought the salmon leaping back

The grizzly bears on the west coast of Canada’s Great Bear Rainforest are smaller than you might expect. They’re not the clumsy, burly beasts of kids’ cartoons; instead, they’re neatly sized with a soft teddy-bear-like appearance.

We were in British Colombia this summer seeing family, and spent as much of that as our budgets would allow on indigenous-led wildlife tours. On the day we spotted the grizzly bears, our guide said that their smaller frame might be because their diets lack salmon from the rivers. They have learned not to expect it.

Instead, they forage for crabs and fleshy, fishy invertebrates under the rocks that line the turquoise channels and bays of the coastline. Presumably it’s less calorie efficient than plucking a plump salmon from a shallow inland river.

Why don’t they expect to find salmon? Well, it depends who you ask, but locals have tracked the demise of salmon in British Colombian coastal rivers against the rise of industrial fish farms.

Mother and two cubs: grizzy bears in Canada’s Great Bear Rainforest

We saw dozens of these fish farms on the waters around Tofino, on Vancouver Island’s west coast. We saw fewer north of the island, around Alert Bay. A few years ago there were twenty-three such farms in that area. Today there are only three. That’s because of a group of determined First Nations people, as I will explain.

And with fewer farms, the salmon are bouncing back. Over the last year, the numbers of salmon have leapt back to 1997 levels. The joint Canada-US Pacific Salmon Commission has predicted a ‘run’ of around 10 million this year. It’s so many, in fact, that the local authorities have re-opened Fraser River for recreational anglers, as covered by CBC News.

While the cause of the rebounding population hasn’t been proven, Living Oceans reviewed the 2024 data and noted: “explosive salmon returns up to 20 times greater than previous generations in one region of the coast and that region correlates precisely with where salmon farms were removed.” This happened after First Nations groups stood up to the fishing industry which has been deploying Atlantic salmon farms in their ancestral Pacific waters.

From the surface, these farms just look like circular rings on the top of the water. But inside is a frenzy of fish. Compassion in World Farming says that salmon, which are around 75cm long, can have the equivalent of a bathtub of water each in these facilities.

One of the three remaining fish farms around Alert Bay

And wherever you look in the world, they are problematic. An investigation by Animal Equity into UK fish farms exposed abusive practices. It’s a shocking read which includes the suffocation of live fish and the hiding of dead fish from government officials. In 2023, the Guardian’s Karen McVeigh reported from Iceland on the risks of farmed salmon escaping interbreeding with wild salmon: their offspring mature too soon, undermining their natural breeding patterns.

And then there’s the lice.

Scientists have shown that lice which have spread within fish farms escape and infect the wild salmon. To attempt to counter this, the farms douse the waters with pesticides.

Back on the boat, and as we pass one of the fish farms in Tofino, our tour guide notes darkly that the lice treatment for the salmon is kept in large, unmarked containers. He says the farms aren’t transparent about what substances they’re pouring into these oceanic fish farms. But according to the Guardian, the Norwegian Pollution Control Authority calculated that a medium-sized fish farm can produce as much effluent – in this case, organic waste and pesticides - as a city of 50,000 people.

While it’s normal for mature salmon to encounter lice at some stage in their lives, fish farms release such quantities that they overwhelm juvenile wild salmon. The lice feed on salmon skin, causing open sores that weaken the immune system. Wild juveniles don’t stand a chance. A study in 2001 found that young ‘out-migrating’ Broughton pink salmon were so infected with sea lice that 98% were forecast by researchers to die. They don’t survive long enough to make it back upstream to their breeding grounds, and to nourish the mammals and land.

Salmon are a keystone species. They don’t just feed bears, wolves and birds of prey. They also feed the land. In peak season, their carcasses can be found strewn the forest floors of coastal British Colombia. Wolves only eat part of the fish and discard the rest. What they leave then rots into the ground, passing nutrients into the soil, and nourishing the thick forest habitat of the islands.

Turquoise: the extraordinary beauty of this archipelago

And so, a thriving population of wild salmon is critical not just for the salmon themselves, but for the entire ecosystem. It’s an ecosystem which has been stewarded for thousands of years by the First Nations peoples. And here is another problem with these industrial fish farms. Whose territory are they in anyway?

In 2017 – in what would become known as the Swanson Occupation - a group of First Nations people set out to reclaim the waters that have been theirs for generations. They fought back “not with fists but with truth” as Captain Locky Maclean told Sea Shepherd, an organisation which supported them. Cynically, the fish farm industry told these people that they were the ones trespassing. It took 280 days, but the First Nations were not cowed and eventually the fish farms relented.

The Captain went on to say: “Those who value record salmon runs over record profits, healthy stocks of salmon over stock market highs and First Nations Culture over Aquaculture feed lots, know the true value of wild salmon and traditional culture on the British Colombia coast cannot be quantified.”

‘Resident’ orcas feed on salmon

And that ‘true value’ of wild salmon includes its value to the entire ecosystem: the bears, wolves and birds that have had to learn to live without it, and the forests and soils which have been missing key nutrients.

Last year, the Canadian government announced it would end open net-pen salmon aquaculture in coastal British Columbia by 2029. Progress indeed, but not soon enough. And they are still to release the plan for doing so. All eyes are on them until they do.

In Canada, the First Nations people showed us the way. But fish farms don’t just occur in Canada. What will it take elsewhere? Take a look at the Rethink Fish campaign from Compassion in World Farming on this.

In coming years, I hope to hear reports of the grizzly bears of British Colombia coast fattening up from an influx of salmon in their rivers and bays.

But in the meantime, perhaps we should all be very curious about where the salmon in our shopping trolleys comes from.

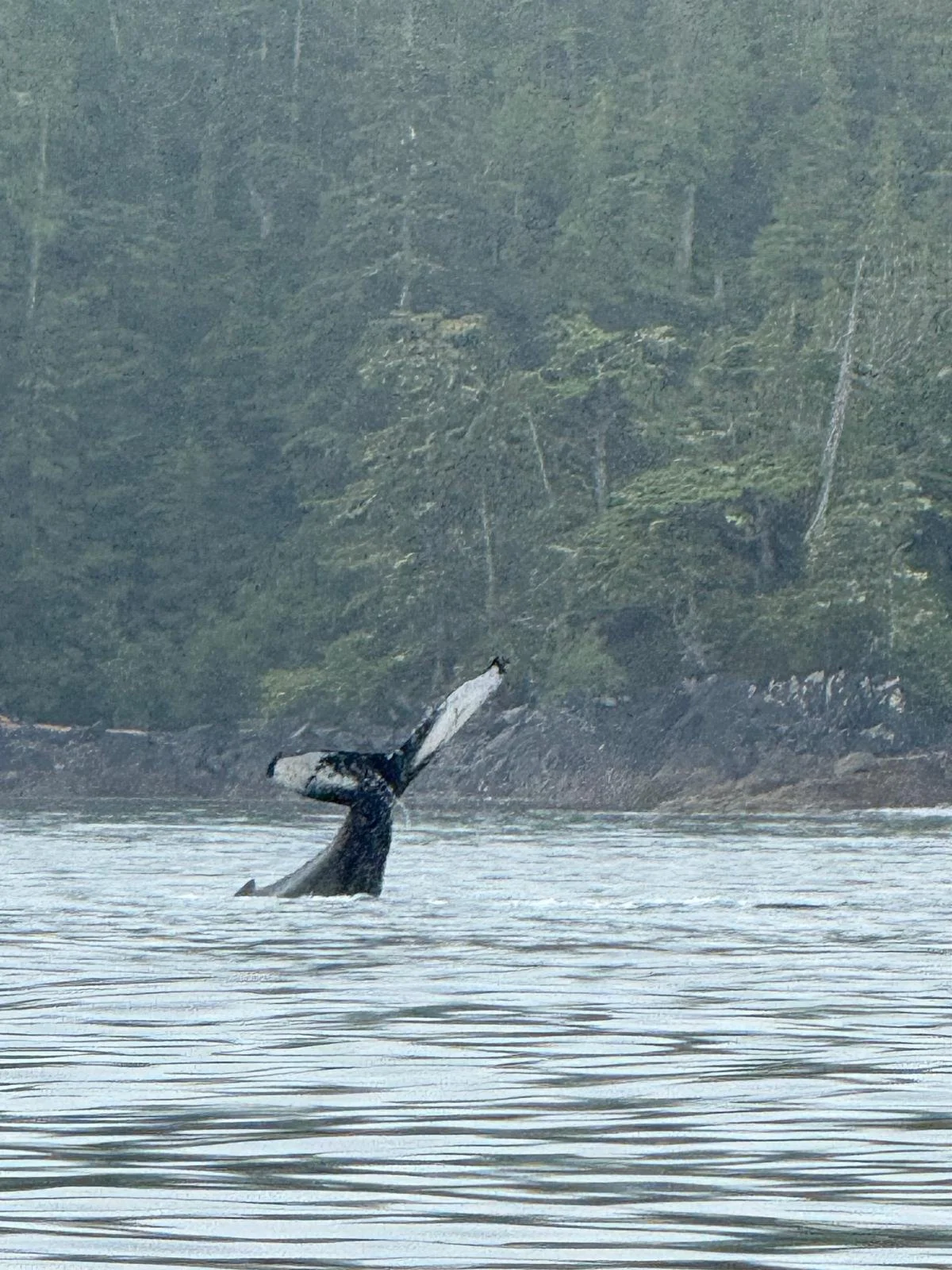

Humpback whales are attracted to these life-rich waters

All image credits: Anna Ford